We've tried to ensure the information displayed here is as accurate as possible. Should there be any inaccuracies, we would be grateful if you could let us know at info@ipohworld.org . All images and content are copyright.

(Please click on the thumbnail for a bigger image.)

An Article From The Michaelian - Life On The Mines

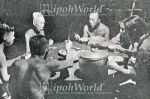

The image and text below are taken from an article by Lin Kok Chiew (Senior Cambridge Class) and published in the St Michael’s Institution 1949 Magazine, “The Michaelian”. The image is a photograoh taken at the Wan Yuen Kongsi owned by Lee Meng Hin, a successful tin miner and the grandfather of the well-known Lee family of Ipoh. led by Tan Sri Lee Oi Hian.

This article relates how the different races, trades and positions live separately but link together to work a successful tin producing mine. It is based on Wan Yuen Mines, from the Kinta Valley, who supplied the photograph entitled “Meal-time at the Kongsi”. The author has chosen to use the polite term 'Mining Labourer' although at the time they would have been generally known by the derogatory name 'Coolies'

The photograph is very unusual as it shows the coolies eating in their quarters (Kongsi), each with a 'Cockerel' bowl and with the traditional large, communal, enamel pot of rice on the table. In addition they would have had an enamel kettle and teapot.

Nelson's victory at Trafalgar, Faraday's discoveries in the field of electrical science, Dalton's work in Chemistry and Newton's laws of motion belong to the world of unforgettable things. Those men and their achievements are remembered, and will be remembered for all time. But their humble collaborators – assistants, subordinates, factotums, etc., – are lost in oblivion. So it is in every field of human activity – in government, in trade, industry and commerce.

When we speak of the wonderful progress of Malaya, we recall the names of the great and pay homage to them, and rightly so, but do we render adequate tribute to the race of humble men and women – Chinese, Indian, Malay, Indonesian, etc. – hewers of jungle trees, drawers of latex and diggers of tin – without whose toil, sweat and courage, Malaya would still be a jungle land inhabited by ....... ?

On Malayan mines, there are the managers, superintendents, engineers, clerks, overseers and labourers. The latter are divided into skilled and unskilled. The former include fitters, founders, carpenters, builders, engine drivers, electricians and tin-ore cleaners. The unskilled labourers dig, carry and manipulate simple machinery. They are under the direction of a Kepala or headman, who does the duties of a field manager. In a Chinese mine, the Kepala has under him Pong San (assistants), Chap Kong (sundry workers), Kongsi Kong (unskilled workmen), as well as Indian labourers and female labourers, in that order of relative importance.

The skilled labourers generally work under cover and the nature of their employment is not unlike that of workers in workshops and factories in towns and cities. However, they miss the amenities of city life. They generally work eight hours a day and get extra pay for working overtime. But they sometimes have to take night shifts. They are paid wages either by the month, varying from $80 to $150, according to the nature and the place of employment, or by the day at slightly higher rates.

Unskilled labourers are paid between $1.25 and $2.50 per day of eight hours' work and are given free food and free sleeping accommodation. They work in the open exposed to the scorching heat of the sun or drenched to the skin in torrential rain, for hours together. Mining is a hazardous occupation. The common causes of accidents are landslides, falling from a height, electrocution and drowning. As all accidents are carefully investigated by the Mines Department, mine managers take every precaution against their occurrence. All workmen are insured against accidents. There were 21 fatal accidents in 1948, the fatality rate being 45 per 1,000 workers.

The quality of the food supplied to mining labourers varies from mine to mine. As a rule, the diet consists of rice, salt fish, vegetables, gourds, roots and beans, and occasionally meat. Three full meals are daily supplied as well as unlimited quantities of tea, and in some cases, a monthly ration of tobacco and a monthly allowance for a hair-cut are given. Twice a month, on the 2nd and 6th days of every moon, are minor feasts when extra meat and fish dishes are supplied, and on national and traditional festivals, dinners with liquor are expected and are always given. On European mines, instead of free meals, a food allowance is given to unskilled labour.

The living accommodation provided for mining labourers cannot be described as comfortable, but has to conform to minimum requirements fixed by the Labour Department as regards sanitation, space and building material. Many labourers live in their own humble homes, squatting on State or other people's land, adjoining the mines. Their dependants cultivate some food crops and rear pigs and poultry to supplement their incomes from the wages they receive.

The majority of mining labourers are unmarried immigrants without education and unable to speak any but their mother-tongue. Some send back regularly part of their earnings to China or India for the maintenance of dependants at home, a few try to save up enough to start petty businesses or to married and settle down, but most labourers spend every cent they earn. Chinese miners are notorious gamblers. In every mining village are gambling dens. The police seem powerless to stop them. A few are opium addicts. Opium smoking, which was a common vice ten or twenty years ago, now claims few addicts. Some miners, having saved up good sums, stop work for a week and go to taste the pleasures of city life. They come back after that, penniless but satisfied, and patiently start life afresh.

Mining labourers do not remain long in one place: they are ever on the move to seek pastures new. Chinese miners as a race are peaceful and comparatively law-abiding. They seldom quarrel or fight, seldom or never get drunk, and few have been convicted of stealing or robbery. But they are clannish in outlook, regard foreigners with suspicion and distrust, and are easily led by political agitators, not because they understand politics but because agitators tickle their clannish and anti-foreign propensities.

Life on a tin-mine for the average miner cannot be regarded as pleasant or conducive to contented living. In out-of-the-way mines malaria and beri-beri are still common diseases, Economic and working conditions still leave much room for improvement. The mine is a vast field for social workers. The Government has done much to bring rates of wages to economic levels, though with higher prices for tin, it may be possible for miners to receive still higher wages. What is wanted is that miners should be encouraged to save and be given facilities for saving. Provident funds and death benefit schemes should be started with government backing. They should also be provided with better forms of amusements. Cinema shows should be made available regularly, and games, like football and basketball, should be encouraged. Social workers, experienced in the ways of labourers, should give talks on personal hygiene, public health, current events and the laws and regulations of the country. Better medical facilities should be provided. In addition to insurance against accidents, health insurance and a sort of old age insurance scheme should be introduced.

Managers, superintendents, engineers and clerks on big mines are generally provided with well-furnished quarters and get comparatively good pay since they have to work and live far from towns or cities. With fewer occasions for spending, they generally manage to save more than people in the towns. But they and their families live a dull, lonely and secluded life far from the civilising influence of the cities. The radio and the telephone, if they are fortunate enough to possess them, are great blessings, keeping them in touch with the rest of the world, the former also providing them with endless entertainment. Managers and engineers are generally able to maintain cars of their own and these enable them to make trips to the town and enjoy the social amenities there. On very big mines, employing a big staff, there are social clubs where members foregather for games, music, literary and educational pursuits and social intercourse. Malayan mines are mostly situated at no great distances from towns and so going for city delights occasions but small inconvenience to car-owners in most cases.

Life for Europeans in remote areas in Malaya today is not enviable. They are in danger of being shot down by bandits lurking in the neighbouring jungle. Many have been killed either on the mines or estates, or on the way, or even at home. The hot moist climate already imposes a great strain on the health of the white man in this country. With the emergency on, Malaya is no paradise for him.

All in all, life on a mine is hard for the men at the top as for those below. Each has his compensations, but my feelings are for the small man, I hope that more and more will be done to improve his lot.

(Senior Cambridge Class)

To read more about St Michael’s Institution, click here.

To read more about Opium smoking, click here.

To read about Cockerel Bowls, click here.